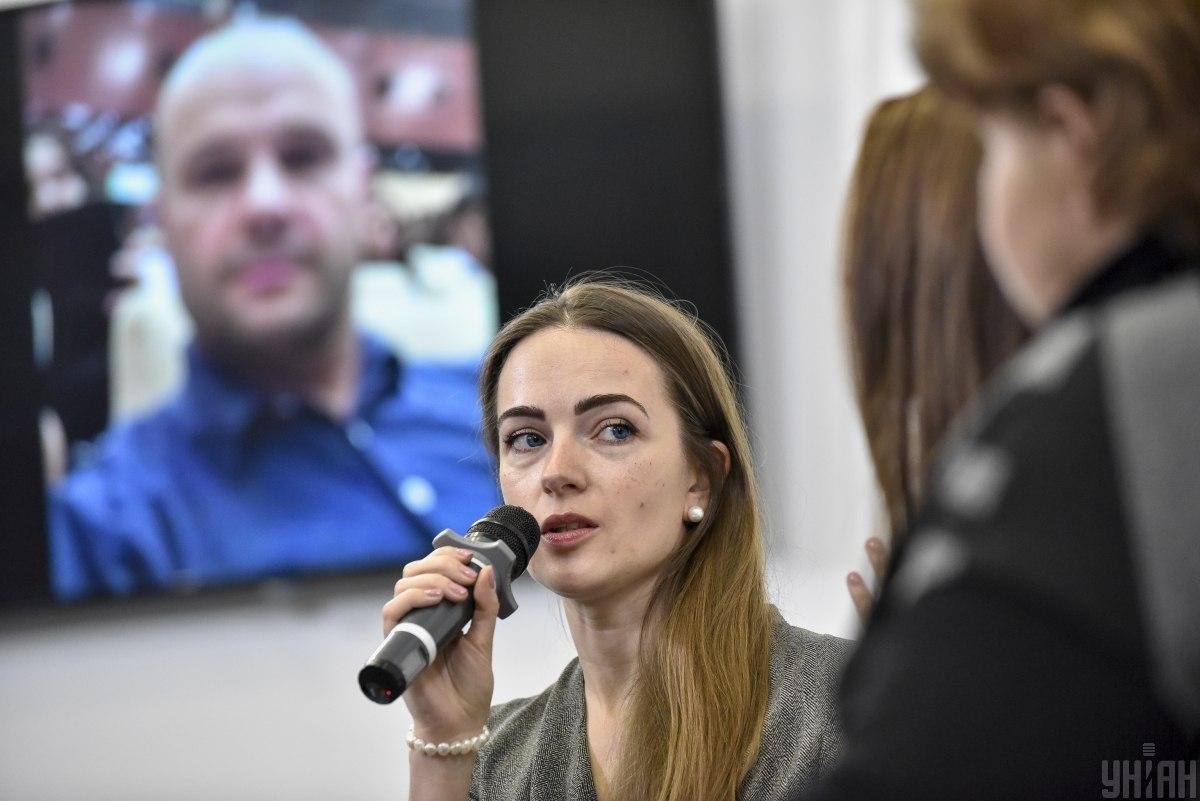

The head of the Center for Civil Liberties Oleksandra Matviychuk has told UNIAN about the ongoing persecution of lawyers in Crimea, the general strategy of the occupying power regarding the Ukrainian peninsula, and what should be done to protect victims of Russian war crimes.

You recently said you were founding of a rights network to support lawyers working on politically motivated cases in the occupied Crimea. Could you tell us more? Who is set to become part of the network, what are your primary tasks?

Lawyers working in Crimea and Russia in the interests of political prisoners or in relation to other forms of political persecution are subjected to pressure, threats, raids, breaches of legal secrecy and privacy, fines, even arrests, and efforts to strip them of licenses. The "Non-Liberty Barometer" in the occupied Ukrainian peninsula is gradually reaching a critical point. When they start persecuting those who protect victims of political persecution, it means that the red mark on that "barometer" has already lit up.

Together with our partners (the Ukrainian Bar Association, the U.S. Bar Association, the Dutch Lawyers for Lawyers, the Moscow Helsinki Group), we have this ambitious idea to build an international network of lawyers to support and protect colleagues suffering from persecution. After all, it's not enough to simply document such cases, draft reports, and recite them on international platforms. Therefore, we will further pay special attention to collective action in solidarity.

Do you plan to cooperate with the Bar Council of Ukraine?

There is a vision of the network, but we are in the process of shaping it up, we're only at the beginning of our path. We are open to working with individual lawyers and associations that are willing to invest their skills, knowledge, and time to protect colleagues in the occupied Ukrainian territories, as well as in Russia.

Should the Bar Council of Ukraine somehow be expressing solidarity with colleagues in Crimea? Maybe they already are?

Even if Ukrainian bar associations did something in Crimea, the efforts were so rare that I can't even think of an example. And that's given me trying to keep track of everything on this topic. The issue of Crimea and Crimean lawyers is not on top agenda of Ukrainian bar associations, and this is an issue. Why should Dutch, Belgian and French lawyers fight for lawyers in Crimea, while Ukrainian colleagues do nothing special about it? We hope to change their attitude. We are very grateful to the Ukrainian Bar Association, which joined our efforts.

So is that persecution of lawyers (raids, fines, etc.) in Crimea a result of rulings by the so-called courts?

I would divide persecution into two categories. First it's action carried out using formally legal repressive mechanisms. These are unlawful arrests and raids, interception of communications, wrongful surveillance, wiretapping, and fabricated cases.

There is also a range of illegal mechanisms. For example, in the occupied peninsula, there are widespread campaigns to compromise targets or persecution where media refer to them as "Devil's advocates protecting terrorists." Again, there are cases of illegal abductions. Let me remind you how the abduction of human rights activist Emir-Usain Kuku unfolded. He was attacked by unidentified perpetrators, thrown into a car, and beaten. Fortunately, there were witnesses to the abduction, so the activist was later released. It turned out the kidnappers were FSB operatives, while no formal report was drawn on his detention.

Of course, there is a difference between lawyers' practices and human rights. But such methods are definitely illegitimate. Even Russia's repressive legislation provides for norms that would allow ill-treatment, torture, and beatings.

So such wrongful practices by unidentified men seems to be a common practice targeting lawyers, right?

Cases where lawyers are abducted and illegally held incommunicado (contrary to the guarantees of procedural status, without notifying the defenders or relatives) are common in Russia. In the occupied Crimea, such abductions have so far only targeted public activists. One can recall the tragic story of the abduction of Crimean Tatar activist Ervin Ibragimov. There is a CCTV footage showing men sporting Russian patrol police officers push Ervin into a van. Years have passed since the incident, while his whereabouts remain unknown to this day.

You know, situations are special and extremely complicated. It's constant pain of families remaining in limbo, between despair and some hope.

It should also be understood that Crimea is now a testing ground for Russia's repressive tactics. If certain practices from mainland regions have not yet reached the Crimea, they might be introduced in the occupied Ukrainian territory in a while.

Photo from UNIAN

So is the situation in occupied Crimea a bit better than in Russia?

I will not say that in Crimea things are better. But in certain regions of Russia it is even worse than in Crimea.

When we were working on the case of the already released Mykola Karpiuk and Stanislav Klykh, which was being considered by a jury, we had a conversation with our Russian colleagues. They told how a jury in Chechnya once decided to hand down a ruling that differed from the one expected of them. At night, jury members were taken out to the woods, where everything was "explained" to them - the next day they all reconsidered their decision.

The question is not where it is better or worse. It's bad everywhere. The question is what we can do to support colleagues who have enough courage to work in politically motivated cases in Russia. It is now an authoritarian country that despises human rights, with no respect for an independent legal profession.

Are there lists of lawyers whose rights are being violated in Crimea and Russia? Are you aware of all such cases?

Our organization has been working with political prisoners for seven years already, so we do know lawyers working on these cases. All the more so if lawyers themselves are victims of persecution. As it was with Emil Kurbedinov, Nikolay Polozov, and Lilia Gemedzhi.

By the way, Lilia Gemedzhi's case isn't over. She is the lawyer for convict Server Mustafayev, who is a coordinator with the "Crimean Solidarity" NGO, now prisoner of conscience, as per Amnesty International. Now Lilia has been targeted in a court ruling, which could bring grounds for prosecution and cost her the license.

We have already seen the same attempt to recall the license of Emil Kurbedinov. The intervention of the UN Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Courts and Lawyers has delivered a "cooling effect" in this story.

That is why we invited Lilia Gemedzhi to address a recent international online discussion on the work of lawyers in Crimea and Russia, attended by the UN Assistant Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers. It was an attempt to draw attention to the topic as a whole and to Lilia's case in particular.

You mentioned fabricated cases targeting lawyers. What articles are usually incriminated? This cannot be terrorism.

In fact, you are very close. Emil Kurbedinov was accused of propaganda or showcasing of paraphernalia or symbols of extremist organizations, for a post on a social network. Branding Crimean Tatars and calling them all terrorists is a tactic Russia pursues. After all, they use anti-terrorist legislation to persecute civic journalists, human rights activists, and members of the Crimean Solidarity initiative.

You see, we are in a state of international armed conflict, which has multiple dimensions to it. Even an information domain... When we talk about persecution of Crimean Tatars, Russia declares in the international arena: "We're not persecuting Crimean Tatars, we're exposing terrorists." Against the background of these statements, people anxiously think of Syria, ISIS, the image of terrorist attacks in European countries. After all, terrorism is a huge problem that cannot be solved within national borders.

That is why I say that Russia is waging a hybrid war applying sophisticated technology. Few talk about this important point, but the question must be raised at the international level. International cooperation and coordinated action are required. Because when Russia, which is part of a number of international organizations involved in fighting terrorism, replaces the concept of combating dissent, it doesn't simply oppress dissenters. It also undermines joint efforts of the international community in the actual fight against terrorism.

Russia should have long been asked to withdraw from all these international organizations or at least faced a number of strict requirements.

Photo from UNIAN

But does it make sense in putting into international limelight the issue of persecution of lawyers? I remember when Mykola Polozov spoke at a PACE session a few years ago about the pressure on lawyers and repression in Crimea, and upon his return he was immediately detained by the FSB. For me, it was a telling story.

You need to understand the context. After World War 2, a global security system was built. Certain things laid down back then (such as the veto power of permanent members to the UN Security Council) were indicators of delayed inefficiency, so one day the system was doomed to fail crash tests.

Even before the occupation of Crimea, we were convinced that international mechanisms protecting human rights could not stop those violations here and now. Had they been able to, chemical weapons would not have been used against the civilian population in Syria. A thousand Muslims would not have been slaughtered in Myanmar. Sanctions would have been imposed on Russia back during the first Chechen war.

After the occupation of Crimea, in the eyes of many foreign politicians, this system has lost its significance, even at a symbolic level. Powers have begun a major arms race and continue their work on nuclear capabilities. After all, they saw that the memoranda and resolutions of the UN General Assembly ensure no protection if they face a powerful and aggressive neighbor.

Indeed, international organizations are unable to provide an adequate response to challenges of modern times. But we can't give up, so we try to set the mechanisms in motion through people's energy.

The Center for Civil Liberties is known for launching mass campaigns where anyone can join the efforts to protect political prisoners in Russia and Crimea, Donbas POWs. We've had the "Let my people go", "Save Oleh Sentsov" and other campaigns. I still often hear someone question our work. People ask, what public actions bring as, after all, people don't get released the next day. I do not tire of explaining that one of the goals of our campaigns is to keep the issue on the agenda. If we fail to hold periodic public demonstrations, no one in the world will pay attention to our problems.

In 2014, when we had 11 political prisoners (now there's 101, despite the release of several dozen), I met with the UN Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights. Having the opportunity, I appealed to him: "Here, we have eleven political prisoners in Russia and the occupied Crimea." He asked, "…thousand?" Then I realized the categories people working globally operate. It takes much effort to draw their attention to our "hundreds and dozens".

That is why we are strengthening human rights efforts with international institutions with a strong public demand. Energy allows our "vehicle" to move in the right direction.

Indeed, Polozov spoke at the PACE session, and then he was arrested by the FSB. Because it's about a long game, part of a great strategy and a constant media focus. After all, foreign politicians, even in countries friendly to Ukraine, don't go to bed or wake up with Ukraine on their mind. Until recently, our people were like that, too. Let us honestly admit that prior to the Russian-Ukrainian war, Ukrainians, in a broad sense, weren't too interested in, say, war in Syria, although the level of destruction, pain, death, and torture is many times higher there.

Photo from UNIAN

What can Ukrainian law enforcement do to support lawyers and their clients who are being persecuted by occupation authorities in Crimea?

Persecution of lawyers and their clients (activists, civic journalists, disloyal or allegedly disloyal citizens) is part of a strategy consisting of the three intertwined trends.

The first is the transformation of the former resort into a powerful military base. Hence the growth of the military contingent, deployment of military hardware, and putting life in Crimea "in militarized mode".

The second one is the forced resettlement of population in order to alter the demographic composition. A military base doesn't need people who lived under Ukrainian democracy. After all, they are beginning to understand that Russia on TV is not the same Russia that came in following the infamous "little green men". Therefore, there are campaigns aimed to colonize Crimea by residents of mainland Russia, replacing the potentially disloyal locals.

The third trend is about how it's being done, including through the mechanisms of repression. It is difficult to live in conditions of non-liberty, where children in schools are instructed to tell on their parents if those consider Crimea part of Ukraine. It's so hard to live this way, so people flee even if they love their small homeland a lot.

Such a purposeful policy by the Russian Federation and war crimes is a matter of violation of international humanitarian law. Taking this into account, it's important to not only think about individual cases or open criminal cases into facts of persecution, but to rise to a whole different level. That is, we need to accumulate these cases in general and lay the foundations for changing the situation in the long run.

Apart from law enforcement, I have an appeal to the Ukrainian parliament, which hasn't found time to establish responsibility for war crimes. We don't even have liability established for crimes against humanity.

What should the Verkhovna Rada do?

As rights activists, we have drafted a bill that amends the Criminal Code and lays down liability for war crimes. It passed the first reading, back in the previous parliament convocation. In the new convocation, the draft was also adopted at first reading only. It was supposed to be put up for a vote in February, but it's not on the agenda, apparently, due to some kind of delay.

People who have survived war crimes in Crimea and Donbas are now waiting for Ukrainian law enforcement and courts to receive a legal instrument to restore justice. It is difficult for me to explain to them why Ukrainian parliament finds time for a bunch of other laws and loud addresses, while failing to pass a law related to war criminals. What's the hindrance? It can't be Putin, right?

The second appeal is to ratify the Rome Statute. In December last year, the prosecutor with the International Criminal Court (ICC) announced that her office had closed a six-year preliminary study of international crimes committed in Ukraine and was ready to ask the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber for permission to launch a probe. When the ISS decision is made (of course this will take time), they will be able to open field offices in Ukraine, interrogate witnesses on their own, collect evidence, and issue arrest warrants. As we have not yet ratified the Rome Statute, Ukraine, not being a member of the ICC, will have no influence on the process. So far, Ukraine has only obligations as the country that sent a one-time declaration, and no rights that full-fledged participants enjoy. This weird situation needs to be fixed.

Iryna Petrenko

If you see a spelling error on our site, select it and press Ctrl+Enter

"tactic" - Google News

February 09, 2021 at 07:50PM

https://ift.tt/2Z1ilBS

Rights activist: Russia's tactic in Crimea is to stigmatize Crimean Tatars - UNIAN

"tactic" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2NLbO9d

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Rights activist: Russia's tactic in Crimea is to stigmatize Crimean Tatars - UNIAN"

Post a Comment