Updated at 11:33 a.m. ET on November 9, 2021.

About six hours after the polls closed on Election Day, the Associated Press made a call in the close race for Virginia governor: Democrat Terry McAuliffe had lost. McAuliffe conceded Wednesday morning, when it became clear he had no realistic path to victory.

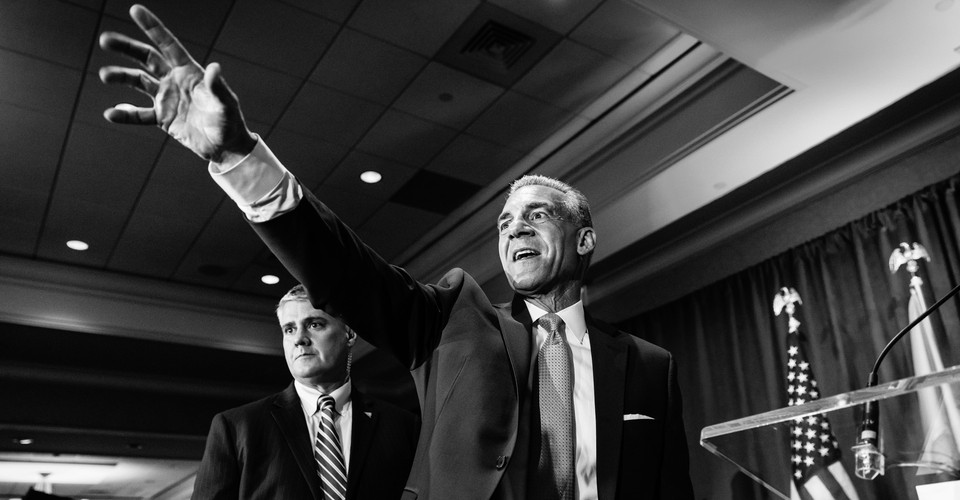

The same has not happened in New Jersey, where the Democratic incumbent, Phil Murphy, defeated Republican State Senator Jack Ciattarelli. Murphy’s margin was closer than expected, but as of Saturday morning, it was larger than Glenn Youngkin’s in Virginia. Like McAuliffe, Ciattarelli came close but has no path to victory. Unlike McAuliffe, however, Ciattarelli has not yet admitted defeat.

This points to a dangerous new dynamic now emerging, in which losing Democrats at the top of a ticket follow one set of rules and losing Republicans follow another. That double standard could put our democracy—and American lives—at risk.

To his credit, Ciattarelli has not—à la Donald Trump—falsely declared victory. Rather, he’s trying to walk a tightrope. Shortly after the race was called, he asked his supporters not to fall “victim to wild conspiracies or online rumors,” and yesterday, under pressure, he made clear that he was not alleging fraud or malfeasance. All the while, however, he has refused to admit defeat.

Ciattarelli’s stance might have been defensible the day after the election, when he could theoretically pin his hopes on a recount. But that ship has sailed. The average state-level recount shifts the margin by about 0.2 percentage points in either direction. Ciattarelli is currently losing by 13 times that amount. And while votes remain to be counted, they’re almost all mail-in ballots, early votes, and provisional ballots—categories that tend to disproportionately favor Democrats.

That’s one reason, in the days since Ciattarelli first told his supporters he still had a path to victory, he’s only fallen further behind. At this point, assuming he doesn’t want to try to overturn a fair and free election, the best he can do is drag out the process for weeks until it reaches its inevitable conclusion.

Before the 2020 elections, such an unnecessary delay would have been merely irresponsible. Now it’s deeply harmful. The Republican Party’s 2024 front-runner continues to repeat his false claims that the last election was stolen, and his base continues to believe them. Nor is the Big Lie, and the violence that has accompanied it, limited to red states. Fifteen of the January 6 defendants are from New Jersey, and many more likely participated in the attack on the Capitol without getting charged with any crimes.

Conspiracy theories about New Jersey’s election are thriving on right-wing social media. Out-of-context reports and videos are being used to cast doubt on the election’s integrity. A Facebook group called “AuditNJ” already has 50,000 members—a particularly disturbing development given Facebook’s role in spreading 2020-election conspiracies.

Ciattarelli may not be actively fanning the flames, but by refusing to acknowledge his loss, he’s giving them plenty of room to erupt on their own. In a best-case scenario, the New Jersey election will be used by national Republicans to further insinuate, completely falsely, that any close election they lose is fraudulent. In a worst-case scenario, Ciattarelli’s refusal to concede will fracture a state and lead to violence.

The rules governing candidates’ concessions have always been implicit. But for more than 100 years, they were generally agreed upon by politicians of both parties. Both parties—and the civic institutions that hold them accountable—must reestablish those standards before it’s too late.

First, there’s the question of when campaigns should concede. After Al Gore’s 2000 concession and subsequent retraction, it’s unrealistic to think candidates in close races should always admit defeat before midnight on Election Day. But once the overwhelming majority of votes are counted—and certainly once networks have called the race—the losing candidate has the burden of either mapping out a realistic path to victory or acknowledging that none exists. Conceding only after exhausting every frivolous legal challenge is barely better than not conceding at all.

This applies to candidates of both parties. Democrat Steve Sweeney, president of the New Jersey state Senate, has yet to admit defeat after losing in a shocking upset last week. He ought to deliver a concession of his own. But Sweeney’s failure to concede does not excuse Ciattarelli’s. Sweeney is not at the top of the ticket, and Republicans, after January 6 and Trump’s endless campaign against the legitimacy of the 2020 election, have a unique obligation to persuade their base to trust legitimate election results, even and especially when they lose.

(Nor, contrary to some conservatives’ cynical claims, does Stacey Abrams’s response to her 2018 gubernatorial loss prove that both parties are equally unwilling to admit defeat. Whereas Ciattarelli is losing by 2.7 percent, Abrams lost by 1.4 percent. Whereas Trump provided no evidence of fraud, Abrams provided a great deal of evidence of voter suppression. And although she ended her campaign by condemning the attempted disenfranchisement of her supporters, she also, ultimately and crucially, acknowledged the final result. One can disagree with specific choices she made without conflating those choices with Donald Trump’s decision to falsely declare victory or Ciattarelli’s decision to needlessly allow conspiracy theories to bloom.)

At a moment when election integrity is under attack, how a candidate concedes is just as important as when. Ciattarelli has promised to accept a final result. When he does so, it is not enough to acknowledge that he lost an election. He must acknowledge that he did not lose the election because of fraud. Given that the Republican base remains in thrall to the Big Lie, dismissing online rumors without specifics is insufficient. He should use his concession to debunk individual conspiracy theories in detail, so that a major Republican candidate is on the record defending the legitimacy of a race he lost.

Election administrators can also do their part to make refusing to concede far more difficult. In several swing states in 2020, and in several New Jersey counties in 2021, mail-in ballots were the last to be counted. Because a disproportionate number of Democrats have voted by mail during the coronavirus pandemic, this gave the impression of a sudden swing away from the GOP candidates late in the race, often after the first night of election coverage was over. There’s nothing nefarious about counting mail-in ballots on Wednesday morning, but some states and counties have begun to count them first rather than last, in order to make baseless claims of fraud harder to promote. That’s a good idea—and costs voters nothing in terms of ballot access.

But even more important than the steps taken by election officials will be the attitude of civic institutions—business groups, advocacy organizations, and the media—toward candidates who refuse to concede, or politicians who look the other way as members of their parties do. If the kind of refusal to concede we’re seeing in New Jersey is normalized, with campaign donations, lobbying, and coverage proceeding as though nothing unusual has happened, we’ll be laying the groundwork for the next January 6, and the one after that, and the one after that.

If last week demonstrated how GOP candidates will handle losing marquee elections in blue states like New Jersey, one can only imagine what will happen if Republicans lose close races for governor, Senate, or the White House in states like Florida, Georgia, Arizona, and Texas next year or in 2024. A graceful concession in Virginia provided a welcome whiff of our old normalcy. But as America already knows from experience, a two-party democracy in which only one party admits defeat is not going to be able to preserve the peaceful transfer of power for long.

This piece originally misstated the percent by which Stacey Abrams lost her 2018 gubernatorial race.

"tactic" - Google News

November 09, 2021 at 10:59PM

https://ift.tt/3qm34KP

The Terrifying Dynamic in New Jersey's Gubernatorial Election - The Atlantic

"tactic" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2NLbO9d

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The Terrifying Dynamic in New Jersey's Gubernatorial Election - The Atlantic"

Post a Comment