While a ceasefire had been in effect for six months, sporadic rocket fire – Kassams and mortars – continued to rain down on Israel. Nevertheless, the government had initially preferred quiet. The situation was tenuous but the residents of the South were, for the first time in years, able to leave their homes with some measure of safety. The government wasn’t going to put that at risk so quickly.

In November, though, the calculation changed. The IDF received intelligence that Hamas was digging a terror tunnel across the border into Israel similar to the one that had been used two-and-a-half years earlier to kidnap Gilad Schalit, a soldier in the Armored Corps. Schalit was still being held by Hamas somewhere in Gaza and the IDF decided that the “ticking tunnel” – as it was being called – had to be destroyed.

An elite IDF force from the Paratroopers’ Brigade was sent across the border near the home under which the tunnel was being dug. In a subsequent firefight, a few Palestinian gunmen were killed. At one point, a large bomb went off in the home, bringing down the structure and collapsing the tunnel.

The Hamas response and rocket onslaught was immediate. Dozens of Kassams, Katyushas and mortar shells pounded the South, reaching as far as Ashdod. A rocket attack led to an Israeli Air Force bombing and then more rockets and more airstrikes. By mid-December the truce – tahdiya in Arabic – had completely fallen apart.

Only a handful of people knew that at the same time as Israeli diplomats were trying to salvage the ceasefire with Egyptian assistance, the Shin Bet (Israel Security Agency) and the IAF were busy building a bank of Hamas targets – headquarters, arms caches, command posts, tunnel openings and rocket launchers. Homes, schools, hospitals, mosques – everything was being used by Hamas to hide their weapons and everything was being added to the IDF list.

On December 27, at 11:30 a.m., what would become known as “Operation Cast Lead” was launched with the bombing of 50 different targets by dozens of IAF fighter jets and attack helicopters. The planes reported “Alpha Hits,” air force lingo for direct hits on their targets. Some 30 minutes later, a second wave of 60 jets and helicopters struck another 60 targets, including underground rocket launchers – placed inside bunkers and missile silos – that had been fitted with timers.

if(window.location.pathname.indexOf("656089") != -1){console.log("hedva connatix");document.getElementsByClassName("divConnatix")[0].style.display ="none";}

In all, more than 170 targets were hit by IAF aircraft throughout that first day. Palestinians reported more than 200 Gazans killed and another 800 wounded.

A YOUNG man stands in his home in Sderot, struck by a rocket fired from Gaza Strip during Operation Cast Lead in 2009. (Photo credit: Reuters)

A YOUNG man stands in his home in Sderot, struck by a rocket fired from Gaza Strip during Operation Cast Lead in 2009. (Photo credit: Reuters)OPERATION CAST LEAD would be remembered as the first large-scale war in Gaza since Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from the Strip three years earlier. It would also go down in history for the United Nations fact-finding mission known as the Goldstone Report that would be established and accuse Israel of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Ahead of the operation, Israeli intelligence agencies knew they had to adapt. Since the withdrawal from Gaza three years earlier, they no longer had a physical presence on the ground inside the now Hamas-controlled territory. While they could use spies and electronic sensors to identify targets, they would not be able to know – in real time – what was happening inside a specific target.

What the IDF knew was that Hamas was storing its weapons in homes, in apartment buildings and under schools, mosques and hospitals. If a war erupted, Israel had to find a way to attack the targets while, at the same time, reducing civilian casualties and collateral damage.

Recognizing the challenge, the Shin Bet did something new: it created lists of phone numbers belonging to the owners of the homes, office buildings and hospitals throughout the Gaza Strip. It was a Sisyphean effort never undertaken by another military, but Israel knew it didn’t have a choice.

While collecting the phone numbers was difficult, their use was supposed to be simple. The IDF knew that there were basically two categories of targets. The first were terrorists: Palestinians perpetrating an attack or in the midst of planning one. Those people were not going to get called before being attacked. To successfully hit them, Israel needed to retain the element of surprise even if that meant some innocent civilians would unfortunately be caught in the crosshairs.

The second category included the homes, apartment buildings, offices, mosques and other civilian buildings where Hamas and Islamic Jihad had stored their weapons, set up command posts or used as cover to hide a cross-border terror tunnel. These were the targets that would get phone calls in order to give the people inside the opportunity to leave.

“We identified thousands of targets thanks to our agents on the ground,” explained Victor Ben-Ami, a 30-year veteran of the Shin Bet, who was involved in the effort. “We had a list of warehouses, factories and buildings with the understanding that the enemy had a tactic it was using to do everything it could to blend in and hide within civilian infrastructure.”

The intelligence, Ben-Ami recalled, was incredible. “We knew what floor the target we were looking for was located, what color it was, what was there, where the air-conditioning machine was located and more,” he explained.

But because Israel knew that civilians would be inside the buildings, the IDF and Shin Bet created a new operational doctrine. Before attacking, it would take the extra precaution of contacting the building owner or occupant.

The callers had a standard text they read in Arabic that went something like this: “How are you? Is everything okay? This is the Israeli military. We need to bomb your home and we are making every effort to minimize casualties. Please make sure that no one is nearby since in five minutes we will attack.” The line would then go dead.

In every case, an Israeli drone would be hovering above, watching what was happening in the home and nearby. Once it saw people running out of the building, IAF headquarters would give the fighter pilot or attack helicopter the green light to drop their bomb. In some cases, the Palestinians claimed Israeli drones were also used to launch the missiles – although Israel has never officially confirmed that it has attack drones.

Not everyone in the IDF saw eye-to-eye on this new tactic. Col. Pnina Sharvit-Baruch was head of the International Law Department of the Military Advocate General (MAG) Unit as Operation Cast Lead was in the planning stages.

Almost every target was brought to her for approval. In one discussion, one of the other officers around the table suggested skipping the warning stage and attacking the building even at the cost of killing or wounding innocent civilians. The building, the officer explained, had been turned into a military target by Hamas and if people were inside they too were military targets.

The argument was immediately and vehemently shot down by all the participants. “That was the definite fringe minority,” she recalled.

In discussions with combat units, Sharvit-Baruch stressed two reasons why this new tactic was critical for Israel. The first was ethical. Israel, she explained, does not callously attack civilians when they can be spared.

“It is our moral obligation,” she affirmed.

The second reason was of political and diplomatic significance.

“A lot of dead civilians deteriorates the conflict and creates diplomatic international pressure and continues the conflict,” she said. “It harms our interests.”

Ben-Ami agreed.

“Whether we like it or not, this is who we are and how we do things,” he explained. “There is no plan that doesn’t take civilians into consideration. This is who we are.”

AN ISRAELI F-15 fighter jet prepares to take off from a base in the South. F-15s are regularly used in ‘roof knocking’ operations. (Photo Credit: Reuters)

AN ISRAELI F-15 fighter jet prepares to take off from a base in the South. F-15s are regularly used in ‘roof knocking’ operations. (Photo Credit: Reuters)

AN ISRAELI F-15 fighter jet prepares to take off from a base in the South. F-15s are regularly used in ‘roof knocking’ operations. (Photo Credit: Reuters)

AN ISRAELI F-15 fighter jet prepares to take off from a base in the South. F-15s are regularly used in ‘roof knocking’ operations. (Photo Credit: Reuters)FOR THE most part the tactic worked. A building would be brought by the Shin Bet to the Southern Command’s Attack Center where it would be added to the list of targets. There, on the second floor of a plain-looking gray structure in the Beersheba-based headquarters, the IDF soldiers and Shin Bet analysts would discuss what to do and how to attack.

The IDF officers would allocate the necessary attack platform and ensure it was available. Once the mission was approved, an Arabic-speaking intelligence officer would call the owner. The drone would show that the people inside the building had left, the soldiers in the IDF command center would count the number of people who had left, ensuring the number matched up with the intelligence they had received, and they would then give the IAF the green light to attack.

The type of bomb used was adapted based on the target. If it was a private home with an arms cache hidden in the basement, the bomb needed to be capable of penetrating the roof and other floors and only detonate once it hit the basement. If the target was on the second floor, it needed to be a bomb that could be launched into a window and just destroy the second floor but nothing else. Success was often measured by the number of secondary explosions, caused by the amount of explosives hidden under the home.

For the first 40 strikes, everything worked smoothly. Some officers privately wondered among themselves why the Palestinians didn’t go to the roof and try to prevent the bombing.

“We knew that if they did that we would have to call off the strike,” one of the military planners at the time recalled.

Calls were made and empty buildings were struck. But then one day, the officer’s fears came true. One of the Palestinians, whose two-story home was a known Hamas weapons storage center, told the Israeli intelligence officer that he would not leave. Word was circulating around Gaza about the new tactic and people knew that exiting the building would mean not having a home to return to.

The family climbed to the roof, knowing a drone was above, and started making indecent gestures at the Israeli aircraft.

A disagreement broke out in the command center. Some of the officers thought Israel needed to go ahead with the attack.

“If we don’t attack we will lose deterrence,” argued one of the officers, a veteran combat soldier from the IDF’s Nahal Infantry Brigade.

Others pushed back. The Jewish state, they said, couldn’t strike a building while knowing there were still civilians inside. The commander of the Southern Command was updated and the issue eventually made its way up to the chief of staff. Both agreed the strike could not go forward. It was called off.

The next day, another Palestinian refused to leave his home and the surveillance drone showed he had also climbed up to the roof. The commanders in the Attack Center watched the live feed with curiosity. In truth they didn’t know what to do.

On the one hand, they were dealing with a legitimate military target. Yes, it had been a house or an apartment building. But once it was being used for military purposes it had morphed into a military target according to the laws of war. The question now was about “proportionality” – a rule prohibiting attacks that may cause loss of life in excess of the military gain from the attack. This was a legal question that required constant consultations with Sharvit-Baruch and her team of lawyers.

Zvika Fogel, a retired brigadier-general, was in the war room that day. A reservist, Fogel had served as deputy commander of the Southern Command in the early 2000s. When Cast Lead broke out, Fogel was called up to run the Attack Center. Every target had to be signed off by him, whether a home, mosque or terrorist on a motorbike fleeing a just-used rocket launcher.

This war hit close to home for Fogel. On January 5, an IDF Merkava tank shot a shell at a building in the Jabalya refugee camp in northern Gaza. The tank crew had mistakenly identified movement in the structure for Hamas terrorists when they were actually Israeli infantry soldiers from the Golani Brigade. Three troops were killed; 24 more were wounded.

Fogel oversaw the evacuation of the wounded. It would be remembered as one of the more complicated evacuations in IDF history. Once the tank had fired its shell, Hamas terrorists opened fire in the direction of the tank and the building and the whole street became a war zone, making it difficult to get the wounded out of the building.

The IDF launched artillery shells to create a smokescreen and provide cover for the troops to get out of the densely populated area and into the open where helicopters were trying to land to fly the wounded across the border to Israeli hospitals.

As he was overseeing the complex operation, Fogel had no clue that one of the wounded was his own son Dor who had been inside the building when the tank shell struck. Thankfully, he sustained only light injuries. IDF SOLDIERS carry light anti-tank weapons as they prepare to send more ammunition to their counterparts in the Strip. (Photo Credit: BAZ RATNER/REUTERS)

IDF SOLDIERS carry light anti-tank weapons as they prepare to send more ammunition to their counterparts in the Strip. (Photo Credit: BAZ RATNER/REUTERS)

IDF SOLDIERS carry light anti-tank weapons as they prepare to send more ammunition to their counterparts in the Strip. (Photo Credit: BAZ RATNER/REUTERS)

IDF SOLDIERS carry light anti-tank weapons as they prepare to send more ammunition to their counterparts in the Strip. (Photo Credit: BAZ RATNER/REUTERS)AFTER THE first time one of the telephoned Palestinians refused to leave his home, Fogel gathered his men in the Attack Center for a consultation on what to do. The home was a legitimate target and had been authorized by Sharvit-Baruch’s team. On the other hand, Fogel knew that attacking would incur too many civilian casualties and whatever tactical gain Israel might achieve from the bombing, it would be for naught.

One of the officers recalled the “Neighbor Procedure,” a controversial tactic employed by infantry units during operations in the West Bank in the beginning of the Second Intifada.

The procedure, which was eventually banned by the High Court of Justice, involved Israeli soldiers sending a neighbor or relative of a wanted Palestinian terror suspect to knock on their door before going in themselves. The idea was that the terror suspect wouldn’t open fire if they knew their cousin or neighbor was standing outside.

While that couldn’t be applied in the same way in Gaza – IDF troops were not always going to be on the ground – the officers started throwing around different ways to achieve the same goal: minimize casualties, on the Israeli side and Palestinian side as well.

“The Neighbor Procedure was an effort used to minimize harm to our soldiers and we thought how could we take it and do something else that could reduce harm to Palestinian civilians,” Fogel recounted.

Fogel was highly motivated to find a solution. In 1996, he was commander of an artillery brigade operating in Lebanon during Operation Grapes of Wrath, started with the objective of stopping Hezbollah rocket fire into northern Israel.

Israel was determined to fight and push Hezbollah far from the border. But seven days into the operation, artillery shells fired by another unit to provide cover for an elite commando team operating in Lebanon accidentally hit a UN compound where Lebanese civilians had sought refuge. Over 100 civilians were reported killed.

While Fogel had not been involved in the assault, what happened next taught him a lesson. Later that day, in New York, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1052, calling for an immediate ceasefire. Israel, which started the operation with a legitimate cause – to defend its own people – came under harsh international criticism. Within days, the operation was over.

Now, 12 years later, Fogel was again fighting in an operation that had been launched to defend Israeli citizens and again was facing a similar problem like in Grapes of Wrath. Civilian casualties would undermine Israel’s legitimacy to act. The world would condemn the country and the government would ultimately succumb to the pressure and stop the IDF.

A couple of days later, when another Palestinian refused to evacuate his house, one of the officers on Fogel’s team came up with an innovative idea. He suggested sending an F-15 or F-16 to dip low over the home in Gaza, to break the sound barrier and try to scare the people inside.

Another officer had a different idea. The house was next to an empty field.

“Why don’t we have a helicopter fire some warning shots into the empty field right next to the house,” the officer suggested.

The Southern Command officers liked the idea and tried it out. It worked and the residents fled the building. The problem was that the IDF would not always have empty lots next to structures it wanted to attack. It needed to come up with a better method.

“It was kind of like what we would do with a terror suspect who refused to leave his home in the West Bank,” the former Nahal Brigade officer who was stationed in the Attack Center explained. “We would first fire a standard 5.56 mm machine gun bullet at the door. If that didn’t work, we would fire a heavier cannon and if that didn’t work, we would throw a grenade.”

After a few more times, the IDF had refined the tactic. It selected a missile developed by Israel Aerospace Industries known for being small, accurate and capable of being configured to carry a limited amount of explosives.

After calling and encountering a refusal to leave the home, the air force will first fire one of these missiles on the roof. It will usually be fired into a corner, far from where people might be standing. In some cases, the missiles can be configured to burst in mid-air, minimizing even more the chances of casualties.

Once the Palestinians experience the “roof knocking,” in almost all cases they flee the building. After the Israeli drones verify the people have left, the Air Force then drops an even heavier bomb, destroying the structure.

While the IDF doesn’t say much about the weapons it uses, pictures of unexploded ordnance circulated online by Gaza residents show a missile with “Mikholit” written on it on Hebrew next to a stamp of Israel Aerospace Industries’ MBT Missile Division. Mikholit in Hebrew is a small paintbrush, like the kind an artist would use for precise painting.

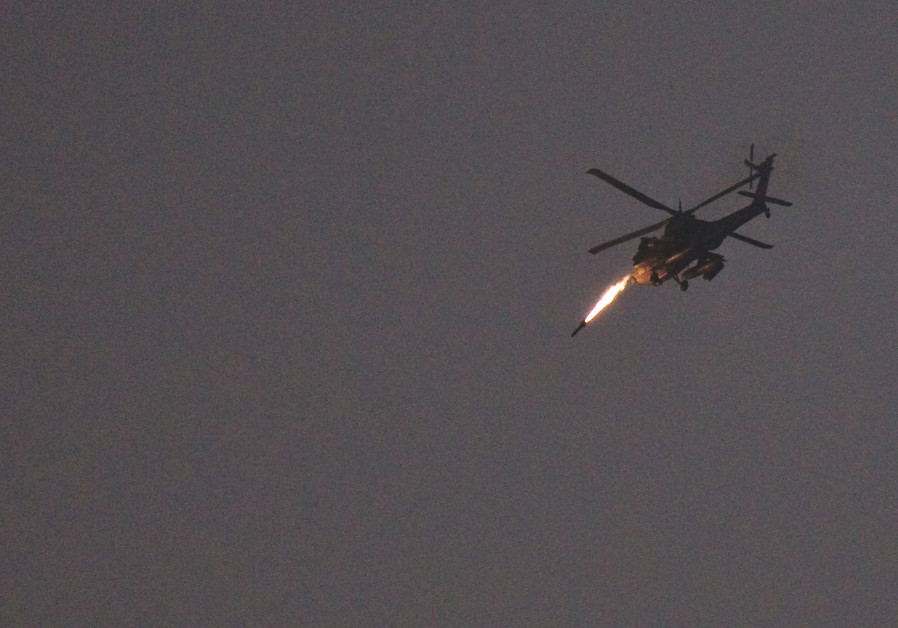

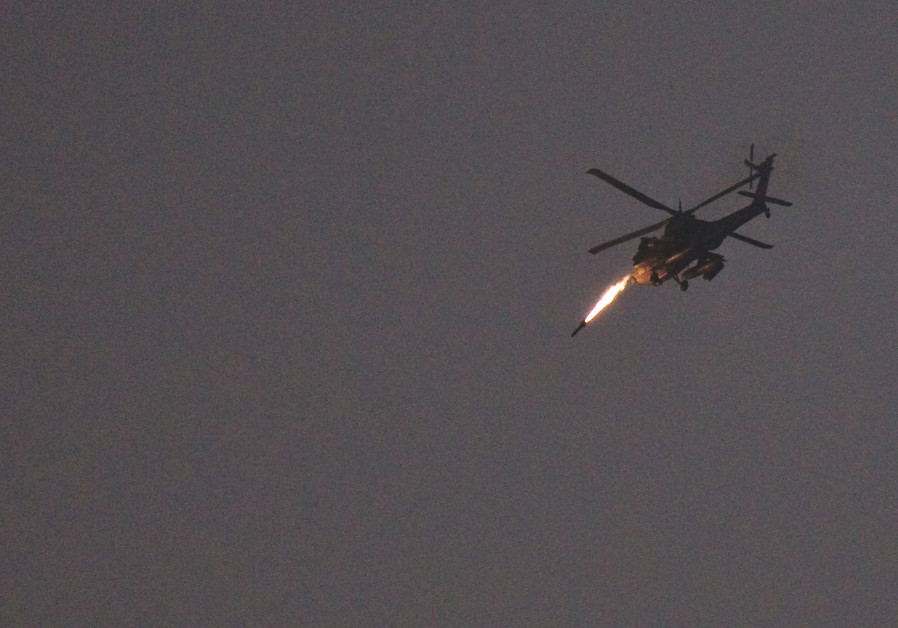

The missile looks exactly like one developed by IAI called “Sledgehammer” which the company says has a range of 20 km., can carry 15-kg. warheads and weighs just 30 kg. It is this missile that Palestinians claim is fired at them from Israeli drones. AN ISRAELI Apache helicopter fires a missile toward the Strip, July 2014. (Photo Credit: NIR ELIAS / REUTERS)

AN ISRAELI Apache helicopter fires a missile toward the Strip, July 2014. (Photo Credit: NIR ELIAS / REUTERS)

AN ISRAELI Apache helicopter fires a missile toward the Strip, July 2014. (Photo Credit: NIR ELIAS / REUTERS)

AN ISRAELI Apache helicopter fires a missile toward the Strip, July 2014. (Photo Credit: NIR ELIAS / REUTERS)DEVELOPMENT OF the roof-knocking tactic was similar to the way the air force adapted to the use of civilian targets in the 1970s in Lebanon. These were the days before Hezbollah when the IDF was fighting against the PLO, which was regularly shelling northern Israel from Lebanon.

At the time, the term “collateral damage” was not as prevalent as it is today. The IAF had just come out of the Yom Kippur War badly beaten – over 100 aircraft were lost – and needed to adapt to a new urban battlefield in Lebanon while rebuilding its morale and deterrence.

“In the war, we were sent to hit runways where there isn’t collateral damage to worry about,” explained retired Brig.-Gen. Uzi Rosen, a former head of the IAF’s Operations Division. “You would take 10 bombs and statistically one would land where it needed to. You didn’t care if they didn’t hit exactly because the target was a runway. Same when you attacked a Syrian battalion on the Golan Heights.”

During the war, Rosen flew in the IAF’s 107th Squadron and on one flight his F-4 Phantom was hit by an Egyptian missile. Despite losing an engine, Rosen succeeded in landing back in Israel. In total, the squadron lost five planes during the war but not a single pilot. Its pilots succeeded in downing 14 enemy aircraft.

After the war, as fighting intensified in Lebanon, Israel found itself facing a new type of enemy – PLO fighters hiding with their Katyusha rockets inside apartment buildings. It presented the IDF with a new tough dilemma.

On the one hand, not attacking meant that within a day or two those same rockets would rain down on Kiryat Shmona. On the other hand, Israel really didn’t have precision-guided munitions yet in its arsenal. Civilians were always around the apartment buildings and attacking would mean extensive collateral damage.

One officer under Rosen came up with the idea to take regular bombs, remove the explosives and fill them instead with cement. This way, the bombs wouldn’t explode but would just cause damage. In other cases, the IAF took 250-kg. bombs and removed half the explosives to minimize the radius blast.

“We were in distress,” Rosen recalled.

The cement bombs were used on hundreds of targets, sometimes successfully and sometimes not as much. But it was all the IAF had until the 1980s, when laser-guided munitions as well as the Maverick – a bomb that used an electro-optical television guidance system – came into service.

Every bomb had its advantages. Laser-guided munitions required a pilot to either be directly over the target or to have troops on the ground “lighting” it up. Electro-optical bombs needed the ability to see the targets as well and sometimes have the navigator – also referred to as the “weapon systems operator” – drive the missile with a joystick all the way to the target.

“It was always a battle between the operational need to destroy a target and the collateral damage challenge,” Rosen remembered. “But it was exactly this need that started leading the defense industries and the army to develop our own precision capabilities.”

Israel’s technological leap came in the mid-1980s with the rollout of the Popeye, developed by Rafael Advanced Defense Systems. What made the Popeye unique was that it came with a smokeless rocket engine – meaning it did not leave a trail – it could be launched from a plane around 100 km. away from a target and could then be driven – via datalink – all the way there by an IAF navigator. Its control could even be handed off to another plane as needed.

Another missile that has become popular in the IAF is the Spike. Also developed by Rafael, Spike’s origins were also in the Yom Kippur War during which the IDF got hammered by Syrian and Egyptian tanks. While Israel ultimately held on to its territory both in the Golan and the Sinai Peninsula, it needed a new weapon to have the upper hand in the event of another conflict.

The Spike – called “Tamuz” in the army – was a secret until just a few years ago. It was operated by two elite units and was fired from armored personnel carriers. The goal was to use the missiles to surprise and stop future tank invasions. IDF bunkers were stocked with the missiles, which came in different sizes and models, and were appreciated for their high degree of accuracy and lethality.

But with warfare changing – tank battles are no longer really a threat to Israel – the IDF needed to find a new use for the Spike and it did, in the air force always on the lookout for new precision-guided munitions.

ALL OF this was done on the fly and in the midst of battle. During the three weeks of Operation Cast Lead, the IDF would go on to drop more than 2.5 million leaflets warning civilians to leave their homes and made more than 165,000 phone calls warning civilians to distance themselves from military targets. The roof-knocking tactic was used dozens of times.

It didn’t go unnoticed. In a report published by the United Nations, Israel’s use of roof-knocking was harshly criticized, with investigators concluding that the “technique is not effective as a warning and constitutes a form of attack against the civilians inhabiting the building.”

One case that drew international condemnation was in July 2018 when two Palestinian teenagers were accidentally killed in a roof-knocking operation on an empty building in Gaza. In a reconstruction of the incident, B’Tselem found that the IAF had fired four warning shots at the building and that the first one had killed the boys as they sat on the roof taking a selfie with their legs dangling over the edge.

The attack, B’Tselem said at the time, showed how roof knocking was not just a warning but was a real attack and therefore needed to conform to international rules of law.

Israel has rejected this assumption.

“Even if warning shots are considered an ‘attack,’ it is incorrect to view them as an attack ‘against civilians’ because they are not fired at civilians, since the objective of their use is to avoid harm to civilians,” explained Sharvit-Baruch, the IDF legal expert.

Despite the criticism, Israel has continued in the years since Cast Lead to use roof-knocking in its Gaza operations, out of a combination of tactical and strategic interests.

Tactically, commanders recognize the need to minimize collateral damage and civilian casualties. Strategically, Israel’s political and military leaders know that when there are fewer casualties, there is less of a chance of a wider escalation with Hamas. Both are clear Israeli interests.

With the International Criminal Court in The Hague now investigating Israel’s 2014 war in Gaza, Israel will once again have to defend its tactics and explain what precautions it takes to minimize civilian casualties, an effort in which roof knocking plays a critical role.

When looking back on the day in 2009 when the IDF came up with roof knocking, it illustrated a determination to adhere to a level of morality not often seen in the midst of battle.

Israel could have taken the easy way out and attacked without phone calls or warning strikes. But it didn’t. The IDF officers and soldiers in the command center adapted to an evolving situation without having a thoroughly thought-out or carefully crafted doctrine for what to do, nor special technology that would guarantee success.

But, they had their objective – to adhere to Jewish values of going the extra mile to protect civilian life – and they acted accordingly. That is the story of roof knocking.

"tactic" - Google News

March 25, 2021 at 07:00PM

https://ift.tt/3soB8DZ

IDF's innovative tactic to avoid civilian casualties in Gaza - The Jerusalem Post

"tactic" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2NLbO9d

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "IDF's innovative tactic to avoid civilian casualties in Gaza - The Jerusalem Post"

Post a Comment