Selling covered calls is a neutral to bullish trading strategy that can help you make money if the stock price doesn't move.

Photo by Getty Images

Key Takeaways

- Selling covered calls is a neutral to bullish strategy that involves selling calls, collecting premium, and rolling the options out

- Covered calls can be used to generate income and offset a portion of the loss should the stock’s price drop

- The choice of strike price plays a major role in the covered call strategy

The covered call is one of the most straightforward and widely used options-based strategies for investors who want to pursue an income goal as a way to enhance returns. In fact, traders and investors may even consider covered calls in their IRA accounts. It’s a pretty basic and straightforward strategy, but there are some things you need to know.

Covered Calls Explained

First, let’s nail down a definition. A covered call is a neutral to bullish strategy where you sell one out-of-the-money (OTM) or at-the-money (ATM) call options contract for every 100 shares of stock you own, collect the premium, and then wait to see if the call is exercised or expires. Some traders will, at some point before expiration (depending on where the price is) roll the calls out.

To create a covered call, you short an OTM call against stock you own. If it expires OTM, you keep the stock and maybe sell another call in a further-out expiration. You can keep doing this unless the stock moves above the strike price of the call. When that happens, you can either let the in-the-money (ITM) call be assigned and deliver the long shares, or buy the short call back before expiration, take a loss on that call, and keep the stock.

Traditionally, the covered call strategy has been used to pursue two goals:

- For most traders, generate income

- For a much smaller number of traders, offset a portion of a stock price’s drop

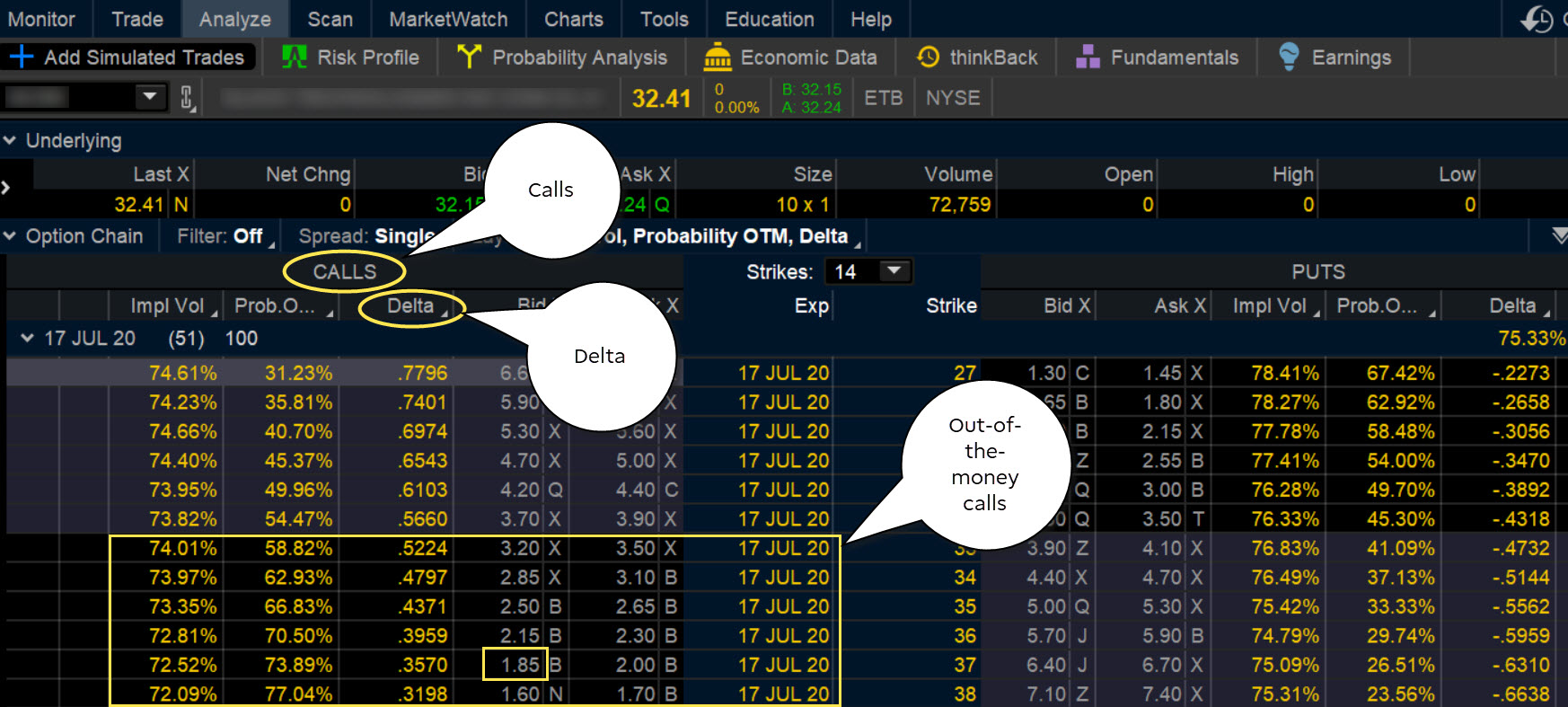

Generate income. We’ll look at a simple covered call example. Say you own 100 shares of XYZ Corp., which is trading around $32. There are several strike prices for each expiration month (see figure 1). For now, let’s look at the calls that are OTM, that is, the strike prices are higher than the current price of the underlying stock. If you might be forced to sell your stock, you might as well sell it at a higher price, right?

Some traders take the OTM approach in hopes of the lowest odds of seeing the stock called away. Others get calls that’re close to the stock price, or ATM, to try get the most cash for the calls.

FIGURE 1: STRIKE SELECTION. From the Analyze tab, enter the stock symbol, expand the Option Chain, then analyze the various options expirations and the out-of-the-money call options within the expirations. Source: the thinkorswim® platform from TD Ameritrade. For illustrative purposes only. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

As long as the stock price remains below the strike price through expiration, the option will likely expire worthless. Options are subject to “time decay,” meaning they will decrease in value in the days and weeks to come (all other factors being equal). As the option seller, this is working in your favor.

You might consider selling a 37-strike call (one option contract typically specifies 100 shares of the underlying stock). You run the “risk” of having to sell your stock for $5 more than the current price, so you should be comfortable with that prospect before entering the trade. But you’ll immediately collect $1.85 per share ($185), minus transaction costs. That’s in addition to whatever the stock may return during this time frame. If the call expires OTM, you can roll the call out to a further expiration.

Keep in mind that the price for which you can sell an OTM call is not necessarily the same from one expiration to the next, mainly because of changes in implied volatility (vol). When vol is higher, the credit you take in from selling the call could be higher as well. But when vol is lower, the credit for the call could be lower, as is the potential income from that covered call.

Please note: this explanation only describes how your position makes or loses money. It doesn’t include transaction fees, and it may not apply to the tax treatment of your position.

| Where’s the stock? | Profit/loss looks like: |

| Stock at or above strike price; short call option is assigned | The strike price minus the stock cost plus the premium collected |

| Stock below strike price; short option is not assigned | The premium collected |

Rolling Your Calls

Offsetting a portion of a stock price’s drop. A covered call can compensate to a small degree if the stock price drops, the short call expires OTM, and the short call’s profit offsets the long stock’s loss. But if the stock drops more than the call price—often only a fraction of the stock price—the covered call strategy can begin to lose money. In fact, the covered call’s maximum possible loss is the price at which you buy the stock, minus the credit(s) from short calls plus transaction costs. The bottom line? If the stock price tanks, the short call offers minimal protection.

Select Your Strikes Accordingly

Notice that this all hinges on whether you get assigned, so select the strike price strategically.

If a stock’s been beaten down and you think a rally is in order, you might decide to forgo the covered call. Even though you may be able to buy back the short call to close it before expiration (or possibly make an adjustment), if you think the stock’s ready for a big move to the upside, it might be better to wait. Conversely, if the underlying had a big run and you think it’s out of steam, then you might more aggressively pursue a covered call.

Once you’re ready to pull the trigger, what strike should you choose? There’s no right answer to this, but here are some ideas to consider:

- Select a strike where you’re comfortable selling the stock. This is about as old-school as you can get.

- Choose a strike price where there’s resistance on the chart. If the stock hits that resistance level and holds steady until expiration, you might hit your full profit potential for that expiration period.

- Pick a strike based on its probability of being ITM at expiration by looking at the delta of the option. For example, a call with a 0.25 delta is read by some traders to imply there’s a 25% chance of it being above the strike and a 75% chance of it being below the strike at expiration. It’s not exact, of course, but some consider it a rough estimate.

Weighing the Risks vs. Benefits

You might be giving up the potential for hitting a home run if XYZ rockets above the strike price, so covered calls may not be appropriate if you think your stock is going to shoot the moon. But in markets that’re moving more incrementally, this strategy could be beneficial. Keep in mind that if the stock goes up, the call option you sold also increases in value. Because you’re short the call, that position is now going against you, but that’s part of the risk you run with an options-based income strategy.

What happens when you hold a covered call until expiration? First, if the stock price goes up, the stock will most likely be called away perhaps netting you an overall profit if the strike price is higher than where you bought the stock. Second, if the stock price moves up near the strike price at expiration you would get to keep the stock and have the gain from keeping the full premium of the now-worthless option.

A covered call has some limits for equity investors and traders because the profits from the stock are capped at the strike price of the option. The real downside here is chance of losing a stock you wanted to keep. Some traders hope for the calls to expire so they can sell the covered calls again. Others are concerned that if they sell calls and the stock runs up dramatically, they could miss the up move.

Covered calls, like all trades, are a study in risk versus return. With the tools available at your fingertips, you could consider covered call strategies to potentially generate income.

Investing Basics: Covered Calls

3:04

"strategy" - Google News

June 13, 2020 at 03:37AM

https://ift.tt/3hpmJmb

Uncovering the Covered Call: An Options Strategy for Enhancing Portfolio Returns - The Ticker Tape

"strategy" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2Ys7QbK

https://ift.tt/2zRd1Yo

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Uncovering the Covered Call: An Options Strategy for Enhancing Portfolio Returns - The Ticker Tape"

Post a Comment