In February 1946, the diplomat George Kennan — then serving as charge d’affaires at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow — authored a 5,000-word telegram analyzing the sources of Soviet conduct and laying out the case for what would become the Cold War strategy of containment. Seventy-five years later, as the United States enters a new era of great-power competition with the People’s Republic of China, War on the Rocks is pleased to publish a landmark essay in this same tradition by acclaimed international relations strategist and renowned Sinologist C. Lea Shea, drawing on his decades of scholarship and service in Democratic and Republican administrations alike.

The defining challenge facing the United States in the 21st century is the rise of China. This is an uncomfortable truth for the Washington foreign policy establishment to admit. Since the turn of the millennium, while the American eagle should have been soaring over the cerulean waters of the Indo-Pacific, its head instead has been buried, ostrich-like, in the Middle East’s sterile sands. But while Washington has been dozing, Beijing has been dreaming — and China’s dreams are the stuff of American nightmares. At long last Americans are slowly rousing from their strategic slumber — awakening to the reality that they have been sleepwalking into disaster. After a long, dark night of geopolitical confusion, can it be morning in America again?

The answer is yes it can — but time is running out. The world is approaching an unprecedented inflection point. Global geopolitics is undergoing a historic paradigm shift. After centuries of Euro-Atlantic supremacy, the balance of power — not only military and economic, but ideological, technological, teleological, and geospatial — is pivoting to the East. Much about this new era remains uncertain, but what is obvious to every sharp-eyed strategist is that the future of the future will be written in Asia. Indeed, it is conceivable that, after decades of the Pax Americana, we are on the cusp not merely of an Eastern Decade or a Pacific Century, but a Sino-Asian Millennium — what political scientists refer to as “The Big SAM.”

It is no exaggeration to say that China’s rise challenges every national interest that the United States has ever had. With its continental economy and cutting-edge technological prowess, Beijing threatens to seep into the nooks and crannies of the liberal international order like butter on an English muffin — clogging the arteries of freedom with the cholesterol of communism and corruption.

We need a strategy — and we need one now.

Sadly, it’s no surprise to see Washington on its back foot against the Chinese Communist Party. Where American officials struggle to think beyond the latest news cycle, leaders in Beijing think in centuries-long historical epochs. While Democrats and Republicans play checkers, China is building supercomputers that can play a fusion of mah-jongg and Monopoly called Mah-japoly. Imagine a world of 144 tiles where Beijing has hotels on Boardwalk and both “Get Out of Jail Free” cards — while America is stuck on Baltic Avenue and hoping for a good Community Chest — and the scope of the present challenge starts to become apparent.

Indeed, it is important to recognize that China is different from any other rival the United States has ever faced. Over the last 250 years, Americans have wrenched their independence from the British empire, waged a bloody civil war that ended the scourge of slavery, thwarted the totalitarian Axis powers in their bid at global domination, and defeated the Soviet empire in a multi-decade Cold War in which the very survival of humanity hung in the balance. By contrast, we can say without hyperbole that the Chinese colossus is at least a million times more dangerous than all of these adversaries put together.

Of course, China is not 10 feet tall. On the contrary, the Chinese system is burdened with debilitating contradictions and crippling weaknesses. Its economy is riddled with corruption. The country’s demographics are a ticking time bomb. This in turn raises the critical yet too-rarely asked question, will China grow old before it grows rich? Indeed, all evidence suggests that the Chinese Communist Party is hurtling toward the ash heap of history. The Long March, the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, Tiananmen Square — all of these past difficulties pale in comparison to the coming crisis of pension payments. So is China rising or is it actually declining? The answer is obvious — and precisely what makes the situation right now so perilous. It also creates a window of opportunity for the United States — but only if we walk through it. Will we do so? It remains to be seen. Have we already done so? In a sense, yes.

Unfortunately, for all the clamor about China in Washington right now, the United States has yet to develop a true strategy commensurate with the challenge. Of course, there has been no shortage of working papers put forward by both government agencies and think tanks. But what is needed is something far more: a comprehensive, nonpartisan vision that truly reconciles America’s ends and means, integrates all aspects of its national power, diagnoses the deepest drivers of Chinese behavior, and knits these disparate threads together into a seamless, whole-of-the-fifty-states (WTFs), civil-military interagency quilt of action. And we must do so with humility.

This is that plan.

First, however, it is necessary to review how we got to where we are today.

America’s original sin in dealing with China occurred 50 years ago when Richard Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, initiated their outreach to Beijing. As idealists possessed by a deep faith in the inherent goodness of human nature, Nixon and Kissinger assumed that the universal desire for freedom, coupled with integration into the global economy, would inevitably induce China to transform itself into a country more or less identical to our own. Indeed, as Kissinger himself pointed out in his visionary first book, A World Restored, no two countries with McDonald’s have ever gone to war. Although the Nixon-Kissinger opening to China yielded some modest ancillary benefits for U.S. strategy, such as the Sino-Soviet rupture and the creation of so-called triangular diplomacy with Washington at its center, the subsequent failure of the Chinese Communist Party to embrace a multi-party democracy as efficient as America’s own reveals how simplistic the Nixon-Kissinger worldview was.

After the end of the Cold War, Washington missed its next opportunity to recalibrate China policy, seduced by naïve visions about the end of history. Indeed, it is all too easy to imagine the alternative path that America could have pursued beginning in the 1990s to hedge against the risk that Beijing might emerge as a systemic rival: reaffirming its Cold War-era alliances with Japan, Australia, and South Korea; reconciling and pursuing new partnerships with rising powers like India and Vietnam; initiating a region-wide economic pact incorporating Asia’s principal economies but excluding China; and weaponizing the information technology revolution to develop the world’s preeminent cyber arsenal. Alas, all opportunities lost.

To make matters worse, in the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks, the United States needlessly threw itself into the quagmire of the Middle East. The fight against Islamist extremism has proved to be a long, unnecessary distraction for American power. In hindsight, it is clear that instead of embroiling itself in places like Afghanistan, the United States should have responded to the menace of al-Qaeda by focusing on the real problem: China. Sadly, instead of launching an amphibious assault on Fujian, Washington wasted blood and treasure trying to thwart further catastrophic terrorist attacks on the American homeland.

Whatever the blunders of the past, however, the United States must now deal with the world as it is, not as it might wish it to be. Happily, in order to build the China strategy that we need, the United States need not look far. On the contrary, Americans can draw inspiration from our best strategic traditions: the idealism of Reagan, the pragmatism of Truman, the breadth of Taft, the warmth of Coolidge, the concision of William Henry Harrison, and the teeth of Teddy Roosevelt.

Of course, the phenomenon of great-power competition is as old as human history itself, with dozens of case studies for policymakers to learn from. As it happens, however, by a remarkable coincidence, the best template for organizing American thinking about the emerging contest with Beijing happens to be the one with which everyone in Washington is already instinctively familiar: the Cold War.

America’s long twilight struggle with the Soviet Union offers several clear lessons that are directly applicable to the present moment, including that this is a contest that will ultimately be decided by transcendent ideals more than raw power, and also that we must rediscover the lost art of ruthless realpolitik. In fact, it is only by cultivating an imagination for tragedy that we can avoid the pitfalls of complacency, confident in the knowledge that history itself is on our side.

Perhaps most importantly, however, the Cold War ought to serve as a reassuring reminder that, for all the dangers inherent in rivalry with China, bloodshed with Beijing is not inevitable. After all, America’s long competition with the Kremlin ended peacefully and without a shot being fired, other than the Korean Peninsula, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Afghanistan, Grenada, Angola, Ethiopia, the Yom Kippur War, the Congo, and a few other minor exceptions. Indeed, this history should make us deeply optimistic about what is in store for the period ahead.

A successful strategy to deal with the China challenge should rest on several pillars.

Ally with allies. America’s extensive network of allies and partners represents a crucial differentiating advantage against China. Indeed, unlike the United States, Beijing cannot count on unbreakable, unshakable bonds with countries with which it is bound by shared values, ranging from Turkey and Hungary to Saudi Arabia and the Philippines. Yet under President Donald Trump, Washington too often picked unnecessary battles with our friends and withdrew from critical international institutions. Under a competitive strategy with China, Washington must get back into the arena.

In practice, this means that Americans need to be in the room where it happens — whether that’s at the World Health Organization, the U.N. Human Rights Council, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the Hanseatic League, Jemaah Islamiyah, or Bohemian Grove.

The ultimate object of American strategy should be the creation of a free, open, and non-proliferated zone of Indo-Pacific excellence — a so-called FONZIE — in which Americans and people they’ve never met can flourish. To achieve the FONZIE, the United States must choose its battles prudently, taking care not to expend precious resources and energies in less-than-vital theaters. Among the flashpoints that must be prioritized are the first and second island chains, the Strait of Malacca, the Himalayas, the Horn of Africa, the prime meridian, the Strait of Gibraltar, the Universal Postal Union, the ice moon of Titan, the upper Zambezi, Proxima Centauri, and the Bay of Fundy. The United States must also devote greater attention to the strategically vital North China Sea, through which upward of 40 percent of the world’s tandem kayaks transit.

One country above all others, however, represents the skeleton key that will unlock the fate of the future: India. As an Asian giant in its own right and a fellow democracy, New Delhi has a unique capacity to work with the United States to preserve a favorable balance of power from the western Pacific to the Swahili Coast of Africa. In many respects, the emerging struggle about the shape of world order is likely to come down to a choice between the aforementioned Sino-Asian Millennium (SAM) led by Beijing, on the one side, versus an Indo-American Millennium (IAM) piloted by the world’s two largest democracies, on the other. In this contest of SAM-IAM, Washington must make clear not only what it is for, but also what it is against: dictatorship, coercion, poverty, corruption, green eggs, and ham.

Another region where the United States should step up its game is the South Pacific. This is a part of the planet with deep, emotional connections to America — from the island-hopping days of World War II to the island-nuking days of Cold War-era atomic tests. Yet today Nauru, Vanuatu, Motunui, and Bucatini are places that most Americans would struggle to find on a map. To address this problem, Congress should back the $13 billion Pacific Geographic Assurance Initiative, which would enable the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command to distribute millions of atlases to every elementary school student in the United States.

Rethink globalization. Over the last quarter century, elected leaders around the world told their people a dangerous fairy tale about globalization — promising that by lowering barriers to trade, they could unleash economic growth that would inevitably benefit all. Although globalization did indeed lift hundreds of millions out of poverty and improve the quality of life in aggregate, including in the United States, the overly simplistic narrative of its boosters — which downplayed the painful trade-offs and costs inherent in its processes — ultimately backfired, creating rich fodder for populists to exploit.

Therefore, it is time for leaders in Washington to level with the American people and finally tell them the full, unvarnished truth: namely, that everything is China’s fault and that, by standing up to Beijing, we will soon be able to bring back good-paying blue-collar jobs in new steel mills and textile factories across America.

Indeed, unlike the war on terror, which was conjured by navel-gazing Washington intellectuals in their wood-paneled Massachusetts Avenue think tanks, the China challenge is a project that is fundamentally about defending and advancing the interests of the American middle class. In America’s heartland, people are not worried about such Beltway abstractions as “preventing another 9/11.” They are focused on the practical issues that affect their families, like the possible establishment of an air defense identification zone in the South China Sea and whether Jakarta is going to be dominated by food delivery apps developed in Silicon Valley or Shanghai.

Sadly, over the past 50 years, Washington recklessly allowed companies to invest trillions of dollars in China as they saw fit. No more. To counter Marxist-Leninism, it is essential that national security experts in Washington — not bourgeois roaders in New York or Palo Alto — make the critical decisions about how and where to allocate American capital and labor. Such a “New Economic Policy” will allow the U.S. government to assert its rightful authority over the so-called “commanding heights” of the private sector. Washington should likewise match China’s strategic vision by developing its own long-term plans for industry — setting five-year national targets in key industries of the future, such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and pig iron.

The United States must also focus on social media, a new and potentially deadly vector of great-power competition. In 2019, for instance, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) forced a Chinese entity to sell its stake in the LGBTQ dating app Grindr. This was a justified measure, given the potential for such applications to enable Chinese intelligence gathering and disinformation, but unfortunately it did not go nearly far enough. Rather than playing defense, the State Department must seize the offensive and establish its own accounts on Tinder, OkCupid, JDate, Bumble, eHarmony, and Ashley Madison. Only by doing so can the United States start to pitch itself as an attractive alternative to the Chinese Communist Party’s Wolf Warrior seductions.

Infrastructure is another area where the United States urgently needs to step up its game, given China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), with its perilous debt-trap diplomacy. In response, Washington should establish its own Belt and Suspenders Initiative (BSI), which would leverage private finance to fund strategically essential projects across the Indo-Pacific, including a high-speed rail network in the Maldives, a deep-water port for Bhutan, and a Bitcoin mine on Pitcairn Island.

As we take these steps, it is necessary to recognize that a broader decoupling of the American and Chinese economies is likely inevitable. This is a daunting prospect. In particular, many governments across the Indo-Pacific and beyond fear having to make a binary choice between Washington, which has long been their primary security partner, and Beijing, which is often their biggest trading partner.

The United States needs to be sensitive to this reality and avoid pressuring any of its friends or partners unduly on this issue. Indeed, there is no reason that any country should have to choose between the United States and China except in certain highly circumscribed areas of heightened rivalry, such as military sales, digital infrastructure, law enforcement, human rights policy, other forms of infrastructure, multinational organizations, maritime policy, resource extraction, intellectual property rights, vaccine diplomacy, video streaming apps, biotechnology, Taiwan, snowmobiles, Kirk versus Picard, circus animals, plastics, and international sporting leagues.

Become more supreme militarily. Repeated wargames suggest that, in the event of a conflict between the United States and China in the western Pacific, Washington could well end up on the losing side of the fight. In the face of China’s anti-access/area denial (A2AD) capabilities, America needs to develop bold new war-fighting concepts of its own, such as accessible access/deniable denial (A2D2); Crouching Panda/Sleepy Eagle (CPSE); Flying Lotus/Downward Dog (FLDD); and Responsible Retaliation/Demolition Derby (R2D2).

Unfortunately, the Department of Defense has a long way to go after decades of distracting conflict in the Middle East. Consider the U.S. Navy. The post-9/11 wars tied up America’s once-mighty surface fleet as a result of the overwhelmingly maritime character of al-Qaeda. Similarly, the intense focus on counter-insurgency led the U.S. Army to neglect its proud tradition of fighting large-scale conventional land wars in East Asia. “More land wars in Asia” should be the Pentagon’s new mantra in this new era of great-power competition.

In practice, this means the Department of Defense needs to embrace reform — divesting expensive legacy platforms in order to build up disruptive new capabilities. To restore their edge against China, U.S. platforms need to become more dispersed, more attritable, and more resilient — kinetically, cybernetically, and interpersonally. It is time to shed expensive manned fighter programs in favor of unmanned, autonomous drones; to reduce the number of vulnerable aircraft carriers in order to develop swarms of stealthy, plankton-powered hypersonic missiles; and to dispose of the military’s innumerable marching bands in favor of a Spotify Premium account.

Promoting innovation inside the Department of Defense will also require wrenching organizational change. A promising development in recent years has been the establishment of entities like the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), which aims to leverage commercially available technology to support the warfighter at the speed of relevance. The next phase of this evolution should be to bring more resources and more of a kinetic focus to this organization — enabling its upgrade to DIU Re-kinetic (DIURetic) — which will deliver results at the speed of nigella sativa.

Cooperate where possible. While the United States and China are engaged in an all-out struggle for global supremacy, there is no reason that we cannot simultaneously cooperate productively in a number of areas. In truth, a few differences over Hong Kong, the South China Sea, the Senkakus, the fate of Taiwan, cyber espionage, genocide in Xinjiang, genetic engineering, AI, hostage-taking, and the militarization of outer space should not present any meaningful obstacle to friendly dialogue on climate change.

The global pandemic provides another encouraging case study in the potential for win-win outcomes, as leaders in Beijing and Washington alike benefited over the past year from pushing as much responsibility as possible for the devastation of COVID-19 away from themselves and onto each other. As the U.S. and Chinese governments face other intractable challenges that they would prefer not to deal with, both sides should explore a wider institutionalization of this arrangement under the aegis of a new Strategic Misdirection and Deflection Dialogue (SMDD).

Even as we pursue avenues for cooperation, however, Americans should be careful not to fall back into old patterns of self-destructive behavior. Realistically, we know how these things happen. It’s a late night at Davos after a grueling day of panels on carbon capture technology. What’s the harm of a quick drink with the delegate from Beijing, you think? Soon you’re reminiscing about old times — escorting China into all the poshest international clubs, taking it easy on weapons sales to Taiwan, doodling little valentines on the margins of your Moleskine with “G-2” at their center. The next thing you know, the harsh light of dawn is breaking over the Alps and you are in a hotel room that isn’t your own, vaguely recalling a promise to outsource the last of America’s semiconductor equipment manufacturing to Shenzhen.

Buy in to bipartisanship. Despite Washington’s alarming polarization, there is an equally striking consensus on Capitol Hill that China is the defining 21st century threat to our way of life and that an all-out mobilization is necessary to stop this menace. This united front draws together everyone from the most progressive Democrats, like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (“AOC”), to the most conservative Republicans, like Sen. Ron Johnson (“RoJo”). Such bipartisan unanimity is deeply encouraging. Indeed, from the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution to the 2002 Iraq War Authorization for Use of Military Force, history teaches us that when such an overwhelming foreign policy consensus emerges in Washington, it is invariably vindicated by subsequent events.

***

At the Cold War’s inception, George Kennan set out a strategy that aligned America’s vital national interests with its deepest values and constitutional traditions. Decades of covert action, support for valiant freedom fighters like Mobutu Sese Seko and Alfredo Stroessner, and intrepid investigations by entrepreneurial members of Congress like Joseph McCarthy all serve as a useful reminder of the U.S. capacity to respond to a foreign authoritarian threat with poise and good sense. A similar effort is needed today.

Indeed, in contrast to the repressive dictatorship of the Chinese Communist Party that brooks no dissent, the United States already possesses exactly those qualities it requires to triumph in the contest with Beijing: a well-functioning democracy whose leaders are firmly committed to the principle of politics stopping at the water’s edge; tolerance for difference and diversity across society; a demonstrated capacity to marshal national resources in the face of catastrophic threats like pandemic disease and climate change; an innovative private sector tirelessly devising new ways to shelter its revenue from the Internal Revenue Service and to deliver highly addictive content directly to the brain of every man, woman, and child on the planet; and the wherewithal to wage long, costly wars with minimal accountability or oversight. Given all of the weapons in the American arsenal, the question is not whether we will win against Beijing, but if we can win twice or even three times over.

The task today in this respect is both clear and straightforward. It is to compete with China without rivalry, to treat Beijing as an adversary bent on our destruction without regarding it as an enemy, to mobilize against the greatest-ever threat to America’s existence while keeping the proper sense of proportion, and to embrace cooperation while carefully avoiding, for lack of a better term, cooperation.

As distinguished students of Chinese civilization appreciate, the Mandarin character for “crisis” is the same word for “opportunity.” Indeed, for the United States, the China crisis is also an opportunity — a chance to crack open the proverbial fortune cookie that providence has delivered to Washington alongside the potluck of great-power competition, and to reflect on the whispers of wisdom within. In this respect, there can be little question that Washington and Beijing are now taking the first steps on what could prove to be a long, happy journey. In doing so, both must remember that success is not a destination but the journey itself — and that every flower blooms in its own sweet time.

C. Lea Shea is one of Washington’s foremost experts on Sino-American relations. He is founder and chairman of the Center for the Study of Great Power Competition, formerly known as the Long War Institute on Counterterrorism and Counterinsurgency and, prior to that, as the New Globalization Initiative. He is author of From Athens to AI, Strategies of Attainment, and a forthcoming book, All Hail RUBIO: Why Rules-Based International Order Will Conquer the Future.

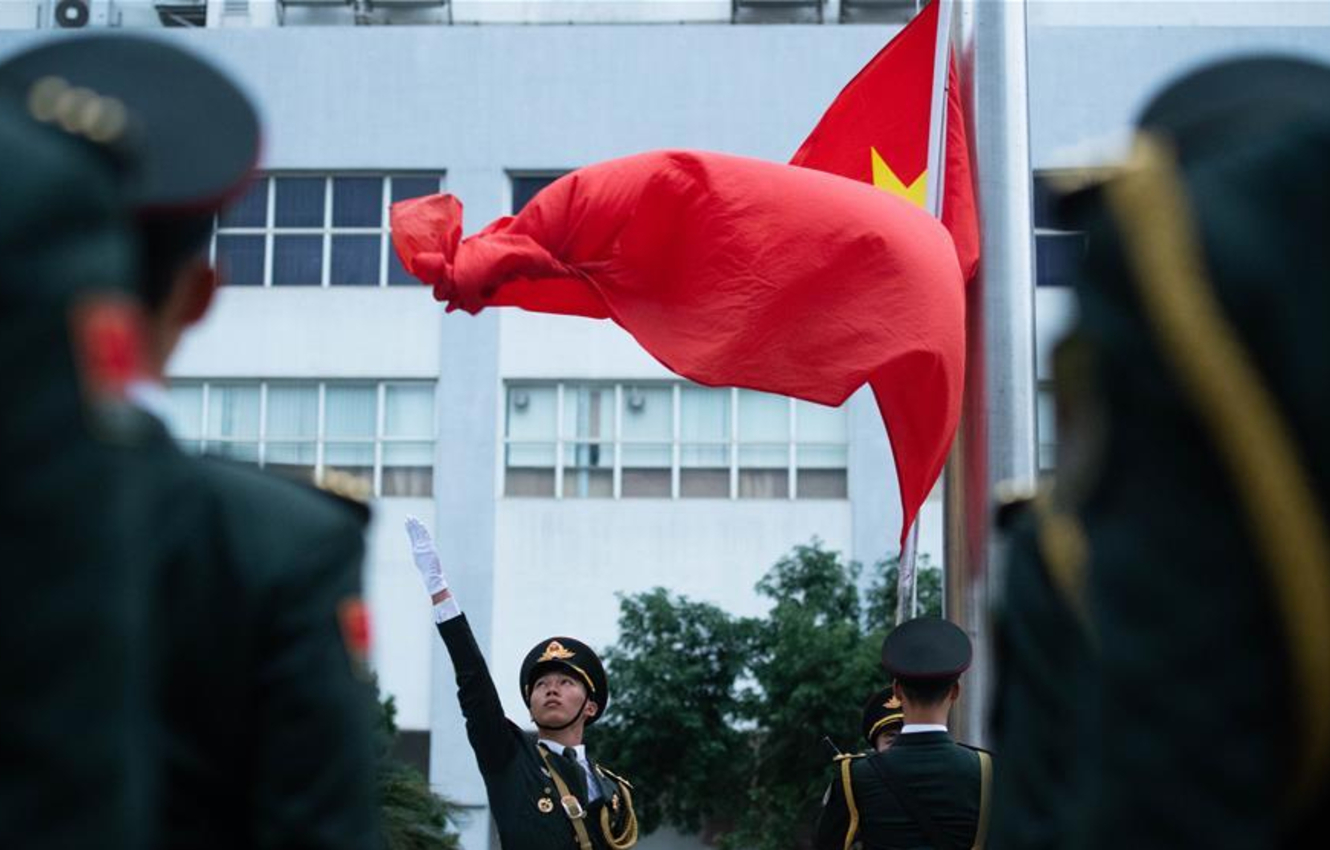

Image: Xinhua (Photo by Cheong Kam Ka)

"strategy" - Google News

April 01, 2021 at 03:00PM

https://ift.tt/39yvasP

The Longest Telegram: A Visionary Blueprint for the Comprehensive Grand Strategy Against China We Need - War on the Rocks

"strategy" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2Ys7QbK

https://ift.tt/2zRd1Yo

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The Longest Telegram: A Visionary Blueprint for the Comprehensive Grand Strategy Against China We Need - War on the Rocks"

Post a Comment